Oxygen-starved 'dead zone' in Gulf nearly as big as Connecticut

The health of the Gulf ecosystem depends in part on choices we make here in Minnesota. (Photo by Todd Kihle, NOAA/NMFS/SEFSC/Galveston Lab)

This year’s oxygen-starved dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico remains stubbornly vast and well above scientists’ target, a stark indicator of the work that still needs to be done to address runoff pollution in the Mississippi River watershed.

At 4,402 square miles (a figure unveiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration earlier this month), the 2025 dead zone covers an area nearly as large as the state of Connecticut. It’s also more than 1,000 miles bigger than the seven-county Twin Cities metro.

"This is a recurring humanmade disaster," says Trevor Russell, FMR’s water program director. "It’s an annual reminder of how the Mississippi River is connected all the way from the headwaters to the Gulf, and how what we do along the river’s earliest stretches impacts communities thousands of miles away."

The dead zone is an area in the Gulf’s waters where oxygen levels are so low that it can kill fish, plants and other marine life (a state known as hypoxia). It’s caused by a buildup of the nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus, much of which washes off farm fields throughout the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin, including in Minnesota.

These nutrients swirl together and barrel downstream, eventually emptying into the Gulf. There they trigger massive algae blooms, which then die off, decompose and take up all of the water’s oxygen. This harms fish, crustaceans and plants in the area that are unable to escape. Mammals and birds that rely on those things as food sources can also suffer. So can both commercial and recreational fishing.

While the dead zone’s area came in slightly below average this summer, its size can swell and contract each year depending, in large part, on two factors.

One, how much water is flowing downstream, referred to as “river discharge.” If there’s a lot of rain in the Upper Midwest throughout spring and early summer, it can result in a larger hypoxic zone.

Two is the amount of excess nutrients in that water (“nutrient loading”). One of the main sources of these nutrients is Midwestern cropland, much of which is left bare and empty in fall, winter and spring — with no plants in the ground that could prevent leftover nitrogen and phosphorus from escaping into nearby the Mississippi River watershed.

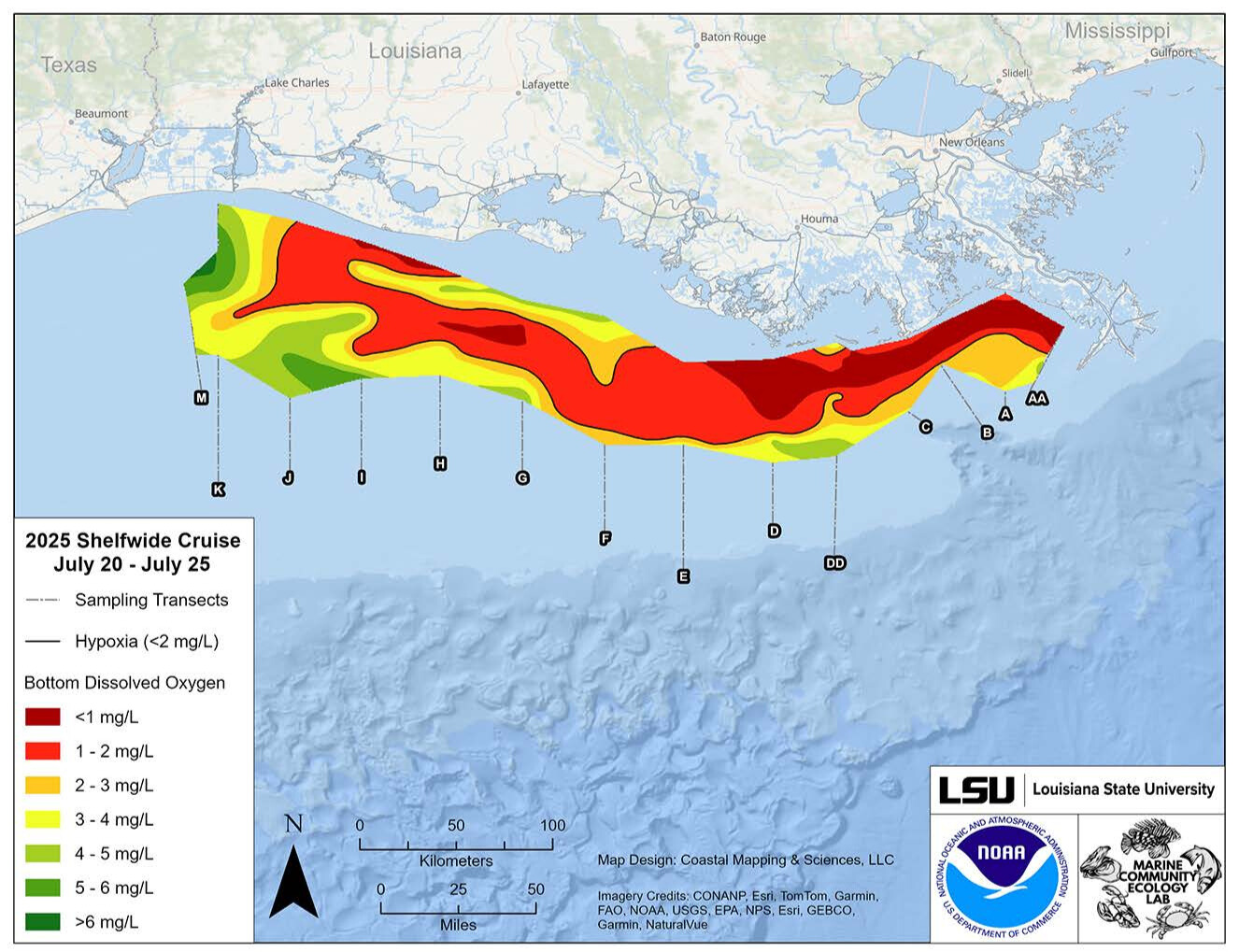

A mapshowing the hypoxic zone in the Gulf, as measured during this summer's survey. (Photo by NOAA/LUMCON/LSU)

Fundamental change needed to shrink dead zone

An interagency Gulf hypoxia task force has set a goal of shrinking the dead zone to 1,900 square miles within the next decade.

For that to happen relying solely on current conservation practices would cost a staggering $2.7 billion a year, Matt Rota, senior policy director at Healthy Gulf, told NOLA.com.

“We need to understand that unless we fundamentally change how we address this pollution, from farming practices to federal and state policies, there is no way we will meet the 2035 goal,” he said.

Clean-water crops like Kernza and winter camelina can help by addressing the former. Their presence on the landscape during the months cropland is usually bare would dramatically cut the amount of nutrients entering the water — in turn, lessening agriculture’s contribution to the Gulf dead zone.

Tracking the impact of these types of measures and making informed decisions about what comes next could be imperiled, however, by the Trump administration’s budget cuts.

As the Louisiana Illuminator reported earlier this summer, “Large sections of NOAA staff have been reduced, and USGS research and data collection funding faces millions of dollars in cutbacks.” Slots for federal agency representatives on the hypoxia-focused task force also remain unfilled.

Whether federal agencies tasked with addressing the dead zone “will have sufficient funding and manpower to gauge if reduction goals are even being met is uncertain,” the news outlet explained.

Regardless of what happens at the federal level, FMR will continue pushing for Minnesota to do its part by expanding clean-water crops, covering the big brown spot and improving the health of the river — from the Twin Cities to the Gulf.